When It Comes to Exercise, Different People Get Different Results

Are you not getting results from your training program? Here's what you can do that is supported by science.

There is no uniform training approach. Two people doing the same training can get very different results. A person can work hard at the gym for months without much progress as their training partner gets stronger with each session.

In exercise research1 there is a term for someone who does not achieve the expected results of a certain type of exercise: non-responder. In one study after another, some participants improve significantly, others do not improve at all, even if they use the same program. 1

It can be frustrating for those who make an effort and don't see the results they want, but we can learn from research in this area to ensure that everyone gets the benefits of exercise.

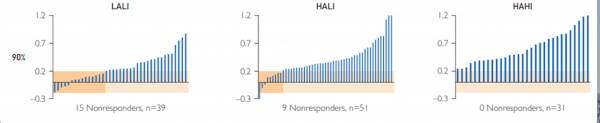

Here is an example of how different individuals are in relation to a particular exercise program.

One hundred and twenty-one adults took part in a 24-week hiking program and trained five times a week. Before the start of the study2, they were randomly divided into three groups:

- A low-volume, low-intensity group that walked an average of 31 minutes per session with an intensity that is considered moderate according to exercise guidelines. I will call it the low group.

- A high-volume, low-intensity group that walked with the same intensity, but approximately twice as long in each session (58 minutes on average) than the first group. I'll call that the middle group.

- A high-volume, high-intensity group that walked with vigorous intensity for about 40 minutes in each session. I will call that the high group.

Cardio fitness was measured several times throughout the study. After six months, each group did the following:

- In the low group, 62% of participants improved their fitness.

- In the middle group, 82% improved their fitness.

- In the high group, 100% of the participants improved their fitness.

On closer inspection, there are also a variety of fitness changes within the groups.

These graphics show how everyone's fitness changed after the program was completed. Each bar represents a person's answer. You can see that some people have improved a lot, others a little, and some people have lost weight.

- In the low group, the range of responses ranged from an 8% decrease in fitness to a 30% improvement.

- The middle group had a range between a 10% loss of fitness and a 43% improvement.

- In the high group, the least responsive participant improved by only 7%, while the top responder improved by a whopping 118%.

Remember that these people did the same exercise program in each group, but their results were very different.

This study3 focused on endurance training for cardiovascular fitness, but it does so in other types of training studies, including interval training and strength training.

In a strength training study 4, for example, the same 12-week program resulted in changes in strength that ranged from no improvement for one person to a 250% increase for another person. There were also significant differences in muscle growth between individuals, with one person reducing their muscle size by 2%, while the fastest responding person increased by 59%.

This effect5 has also been observed in nutritional science, where people on the same diet experience very different amounts of weight loss and sometimes even weight gain.

The reasons for these differences are not obvious. Of course, factors such as sleep, stress, diet, and occasional physical activity can affect a person's response to an exercise program.

The researchers are trying to take these things out of the equation by asking participants to follow a standardized diet or by letting them wear activity trackers when they're not in the laboratory, but it's not possible to fully control them.

Genetic factors certainly play a role too. Research6 shows that about 50% of the response to cardio training is due to genetic differences.

What can we learn from it?

If you're one of the lucky ones who happens to respond well to a particular exercise program, that's great! If not, don't worry. While these results may seem daunting at first, there is good news. If we continue to research, it seems that there are no real non-responders that can be trained. Everyone is improving somehow.

If you don't get the results you expect from your exercise program, keep the following in mind.

When it comes to practice, consistency is key

The most effective program for you is probably the one you run regularly.

In the walking study, the researchers only reported the fitness improvements of those who had attended at least 90% of the training sessions in the six months.

Not everyone who completed the study managed to hold 90% of the sessions. As the researchers declined and included those who attended at least 70% of the sessions, the percentage of people who increased their fitness decreased by about 4% in the lower and middle groups and by about 12% in the high groups.

I would say that 70% are still pretty consistent. This means that these people trained an average of 3.5 sessions per week per week for six months. Most of them improved their fitness. However, more consistency is better. People who attended 4.5 sessions per week (90% of total sessions) were even more likely to improve.

Consistency is probably the most critical factor in achieving the benefits of exercise. Do something every week. If you're struggling with consistency, focus on setting small, achievable goals and creating sustainable exercise habits before you go into the details of the program you're running.

Have the other parts of a healthy lifestyle in place

Get enough sleep, drink enough water, eat plenty of nutritious food, exercise as often as possible throughout the day, and manage your stress.

If you don't have these things well under control, you don't know if it is the exercise program you are not responding to, or if there is something else holding you back in your lifestyle.

If one method doesn't work, try another

Perhaps you have a healthy lifestyle and have been training consistently with lackluster results for several months. What should you do?

Try increasing the intensity or duration of each session. If we look at the walking study again, some participants did not improve their fitness after six months of steady, moderate-intensity exercise.

Nevertheless, all people who trained at a higher intensity improved. Even with moderate intensity, people who increased their volume (doubling the time spent in each session) were more likely to see improvements.

You can also have more sessions throughout the week. In another study7, the researchers found that when people did 60 minutes of cycling 1-2 times a week for six weeks, not everyone improved their fitness.

In this study, there were also people who did the same bike training 4-5 times a week, and all of these people answered. After that, the people who had not improved their fitness repeated the program. This time they added two more sessions a week and all improved.

You could try a different type of training. In one study, the participants completed a three-week endurance sport program and a three-week interval training in a random order. 8

They found that some people did not improve their fitness with one program, but these people improved when they ended the other program.

A number of set and rep protocols9 appear to be effective for strength training for different people. For example, if your goal is to increase muscle mass and the traditional four sets of 8 to 12 reps didn't work for you, your body may respond better to heavier weights and fewer reps, or lighter weights and more reps.

Treat your training as a scientific experiment

Exercise offers a number of different and crucial advantages. It can improve your body composition, reduce your risk of many diseases, improve your performance, brain function and mood, and much more.

Even if you don't see the specific results you expect, You will improve your health and fitness in some way through consistent training.

For example, the researchers had the participants complete a one-year cardio program that worked 45 minutes three days a week. At the end of the program, four different types of cardio fitness were measured.

Here too there was enormous variability in the individual answers. And some of the participants have not improved in all four ways. However, each person in the study showed improvement in at least one aspect of their fitness.10

You may be focusing on the wrong level of results, or you may not be tracking your progress closely enough to see what you are accomplishing. If you don't keep track of what you're doing and how you're progressing, you don't know if your program works for you or not.

Make a list of some of the benefits of exercise that are important to you and keep an eye on each one.

- If you're interested in improving your health, you can track your resting heart rate, blood pressure, or blood sugar.

- For body composition, you can track your body fat percentage or body measurements.

- If fitness and performance are important to you, keep an eye on your time to walk a certain distance, the amount of weight you lift for each exercise, or the number of push-ups or pull-ups you can do.

- Use a simple 1 to 10 scale to assess how you feel every day to get the more subtle (but equally important) benefits of exercise like mood, stress relief, concentration, pain frequency, or energy.

Record this information in a notebook or use a spreadsheet or your phone. Follow a specific program for a few weeks or months, assess how you react, and make changes if necessary.

You will probably be pleasantly surprised at how many ways you improve your body and life through exercise.

Your blood pressure may not have decreased, but your mood may have improved and your 5 km time may have improved. Maybe you haven't lost weight, but your strength has increased and you have gained energy and started to sleep better.

These improvements can motivate you to keep going. If you do this, you will likely find an exercise method that works best for you.

Do not compare yourself to others

It should now be clear that just because your friend has had great results after a certain program does not mean that you will. Concentrate on your progress, not on others' progress.

The bottom line

If you don't see the results you want, try again. If you still don't see any results, try something different. Finally, keep in mind that science is clear. Everyone answers.

If you stick to it consistently, you will get significant benefits.

References

1. Pickering, Craig and John Kiely. "Are there non-responders who play sports – and if so, what should we do about it?" Sports medicine 49, no. 1 (2019): 1-7.

2. Ross, Robert, Louise de Lannoy and Paula J. Stotz. "Separate effects of intensity and amount of training on the interindividual cardiorespiratory fitness reaction." Mayo Clinic, Proceedings 90, No. 11 (2015): 1506-1514.

3. Gurd, Brendon J., Matthew D. Giles, Jacob T. Bonafiglia, James P. Raleigh, John C. Boyd, Jasmin K. Ma, Jason GE Zelt and Trisha D. Scribbans. "Incidence of non-responses and individual response patterns after sprint interval training." Applied Physiology, Nutrition, and Metabolism 41, No. 3 (2016): 229- 234.

4. Hubal, Monica J., Heather Gordish-Dressman, Paul D. Thompson, Thomas B. Price, Eric P. Hoffman, Theodore J. Angelopoulos, Paul M. Gordon et al. "Variability in muscle size and strength gains after one-sided strength training." Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise 37, No. 6 (2005): 964-? 972.

5. Gardner, Christopher D., John F. Trepanowski, Liana C. Del Gobbo, Michelle E. Hauser, Joseph Rigdon, John PA Ioannidis, Manisha Desai and Abby C. King. "Effect of a low-fat versus low-carbohydrate diet on 12-month weight loss in obese adults and the association with genotype pattern or insulin secretion: the randomized clinical trial DIETFITS." Jama, 319, no. 7 (2018): 667-7. 679.

6. Ross, Robert, Bret H. Goodpaster, Lauren G. Koch, Mark A. Sarzynski, Wendy M. Kohrt, Neil M. Johannsen, James S. Skinner et al. "Precision Training Medicine: Understand the Variability of Training Reactions." British Journal of Sports Medicine 53, No. 18 (2019): 1141 & ndash; 1153.

7. Montero, David and Carsten Lundby. "Refuting the Myth of Non-Response to Exercise Training:" Non-Responders "Responding to a Higher Dose of Exercise." The Journal of Physiology 595, No. 11 (2017): 3377-? 3387.

8. Bonafiglia, Jacob T., Mario P. Rotundo, Jonathan P. Whittall, Trisha D. Scribbans, Ryan B. Graham and Brendon J. Gurd. "Inter-individual variability of adaptive responses to endurance and sprint interval training: a randomized crossover study." PloS one 11, no. 12 (2016).

9. Beaven, C. Martyn, Christian J. Cook and Nicholas D. Gill. "Significant strength gains in rugby players following specific resistance training protocols based on individual testosterone responses in saliva." The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research 22, No. 2 (2008): 419-4. 425.

10. Scharhag-Rosenberger, Friederike, Susanne Walitzek, Wilfried Kindermann and Tim Meyer. "Differences in adapting to a year of aerobic endurance training: individual patterns of non-response." Scandinavian Journal of Medicine and Science in Sport 22, No. 1 (2012): 113- 118.